At-Tahajjud

(The Night-Vigil)

for soprano, clarinet, harp & percussion. 50’

“My God! The stars have set, everyone’s eyes are closed, the rulers have locked the gates of the city, and every lover is alone with his beloved; this is when I devote myself to You.”

At-Tahajjud is a cycle of fifteen songs based on the words of Sufi women who lived from the 9th-12th centuries. All texts are drawn from Dhikr an-Niswa Al-Muta ‘Abbidat as-Sufiyyat, a scholarly work complied by Abu ‘Abd ar-Rahman Muhammad ibn al-Husayn as-Sulami in the 12th-century, and published by Fons Vitae as “Early Sufi Women,” with translation and commentary by Rkia Elaroui Cornell. It was commissioned by Anne Harley as part of her ongoing Voices of the Pearl series. Set in the original Arabic, it is structured as an all-night vigil, beginning at dusk with Rabi’a al-Adawiyya’s famous prayer written above, and ending at dawn with words that echo the opening.

It is a comprehensive vision of the spiritual life, featuring a great variety of attitudes towards the divine. As the soul journeys toward its goal, it must undergo many contradictory things. But there is a connecting force that is present every step of the way — unquenchable longing (shajan).

In its theological sense, shajan is a cosmic longing without object. It does not seek satisfaction, but is eternal. According to many Sufi women, it is the only truthful way to approach God. Their practice of ceaseless weeping is a testament to this. As Shawana says, to break off weeping is the same as abandoning love.

I have heard Arabic musicians half-jokingly say that all Arabic songs have the same lyrics: “the Beloved is far away.” At-Tahajjud is no exception. Indeed, as I embarked on the composing of this piece, I wondered where the emotional variety could come from. Outwardly, every poem expresses the same thing — longing for the Beloved. How many ways could I contrive to portray this specific feeling?

But by the end, I found that I had generated more variety in my music than ever before. I had discovered, and have since absorbed into my life, a truth that these women knew a thousand years ago: sorrowful longing is our connection to the infinite, and thus contains all things.

At-Tahajjud, therefore, is a central expression of my musical theology. In this view, shajan is not just one musical mood among many — it is the wellspring from which music itself is drawn. It creates variety and multiplicity, giving the moods their depth and definition — not paving them over with sadness, but granting them their distinctiveness. Shajan is the prism through which the full spectrum of human feeling is refracted.

The cosmic drama of the soul

One of my goals with this piece has been to put forth a different view of the ascetic life, one hopefully closer to the truth of what it really consists.

What motivates the renunciant to spend their life in solitude and prayer, sacrificing most, if not all of their freedoms and comforts? Some aspects are understandable. Anyone can see the appeal of escaping the hectic nonsense of the modern world. The longing for peace is surely universal. And it is not difficult to imagine persons in whom this longing is particularly strong, and who are willing to make large sacrifices in its pursuit.

But most people, I think, imagine the ascetic life as involving a reduction, a simplification, a narrowing, of the range of possible experience and feeling — and that this is merely one of the costs of a more peaceful existence. For some renunciants, this is perhaps true.

However. When giving up the finite in exchange for the infinite, you may get more than you bargained for.

The fact is, the spiritual life opens up a range of experience so vast that it is almost unfathomable to those of us remaining in the world. As Rautavaara says, “Mysticism is only an exceptionally intensive way of experiencing reality.”

But venturing out into the infinite reality means baring one's soul to truth, without ceasing. Just as water carves and reshapes entire continents of stone, truth scours our hearts of all delusion. It is a consuming fire. Deep encounters with it can be inutterably excruciating. And all humans have these encounters, sooner or later. But they are often relegated to rare moments — the major turning points in life — occurring only when it is absolutely necessary.

But for the ascetic, to bare the soul to the whips & scorns of the divine is a daily enterprise. All the trappings of their lifestyle are designed to facilitate this struggle. But what a task! To bear the full totality of the truths of existence, directly in the heart, from dawn to dusk, dusk to dawn, and day after day, year after year — one’s whole life? Surely this is a great emotional labor. Who is able to do it? Only those who are willing, or called, to this titanic challenge. The purpose of the ascetic life is to live constantly immersed in the truth, on behalf of those who cannot.

It is my great hope that the listener of At-Tahajjud can somehow glimpse the cosmic drama unfolding in the hearts of many across time — those living in quiet, hidden places. As we stand on the shore, they set sail across the infinite ocean, suffering in ways unknowable, beholding impossible things, taking flight into distant, ethereal dimensions. Perhaps it is we who are content with little. And perhaps it is they, these Sufi women and others, who can say with Thérèse of Lisieux — “I choose everything.”

Photo credits:

Diego Delso, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=148173462

Henry Ossawa Tanner, “The Annunciation” Philadelphia Museum of Art https://philamuseum.org/collection/object/104384, Public Domain

https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=133819364

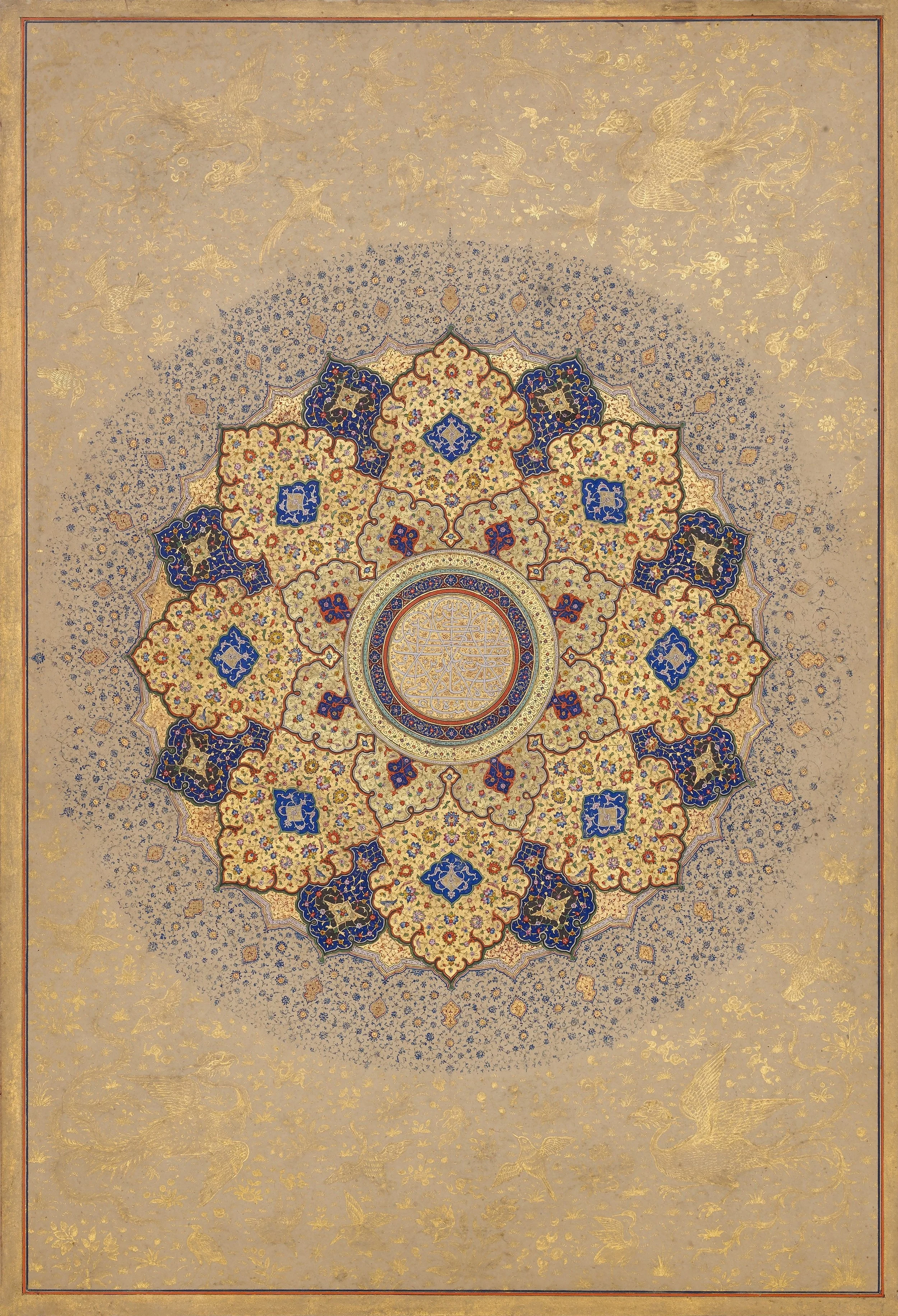

Rosette Bearing the Names and Titles of Shah Jahan, Folio from the Shah Jahan Album. Public Domain

https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/451286

Phillip Capper from Wellington, New Zealand - Alhambra, Granada, Andalucia, Spain, 2 October 2005, CC BY 2.0

https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=2129534